Building an MCP Server for Network Automation: What I Learned from 142 Tools

A deep dive into Model Context Protocol for network engineers

I've been building network automation for a couple of years. Ansible playbooks, Python scripts, REST APIs. They all work. But when Anthropic released the Model Context Protocol (MCP), I saw something different: a way to make AI understand network operations natively.

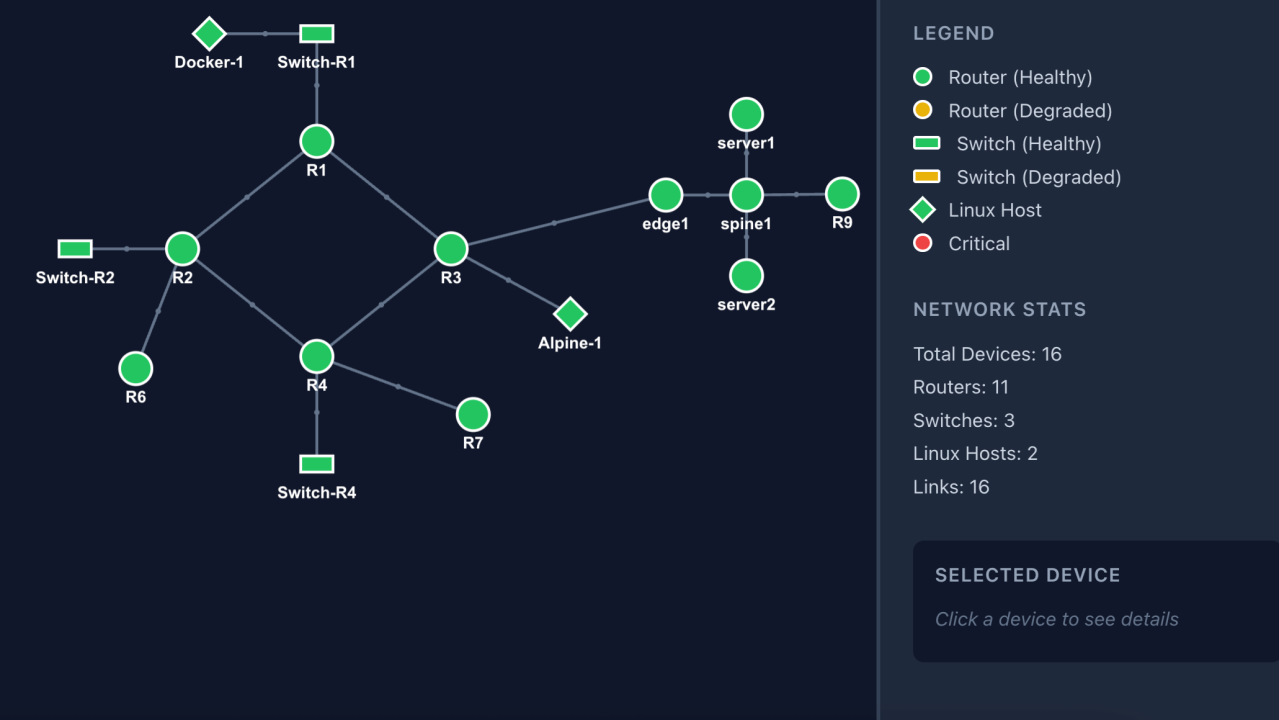

Five months later, I have 142 MCP tools managing 16 lab devices. Here's what MCP actually is, how I architected it, and what I'd do differently.

What MCP Actually Is

MCP is a specification for how AI models interact with external tools. Think of it as a contract between Claude and your automation: "Here are the tools available, here's what they do, here's how to call them."

The key difference from REST APIs:

Discovery → REST uses OpenAPI spec (optional); MCP declares tools at connection

Invocation → REST requires you to construct HTTP requests; MCP lets the AI model decide when/how to call

Composition → REST means you build the workflow; MCP lets AI chain tools as needed

Documentation → REST docs are for humans; MCP docs are for the model (and humans)

When Claude connects to my MCP server, it receives all 142 tool definitions with their parameters, types, and descriptions. It then decides which tools to call based on what I ask—no hardcoded workflows.

The Architecture: FastMCP + Modular Tools

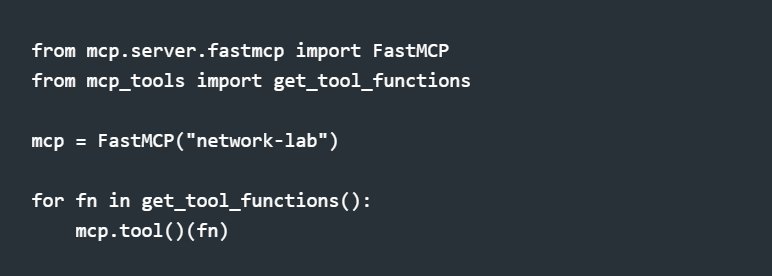

I use Anthropic's FastMCP library for the server. The entire entry point is 18 lines:

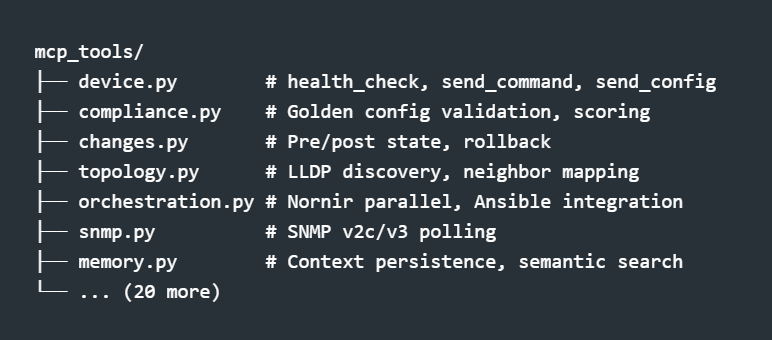

The magic is in the mcp_tools/ package—27 modules organized by function:

Each module exports functions decorated with type hints and docstrings. The get_tool_functions() aggregator collects them all for registration.

Tool Design: What Claude Actually Sees

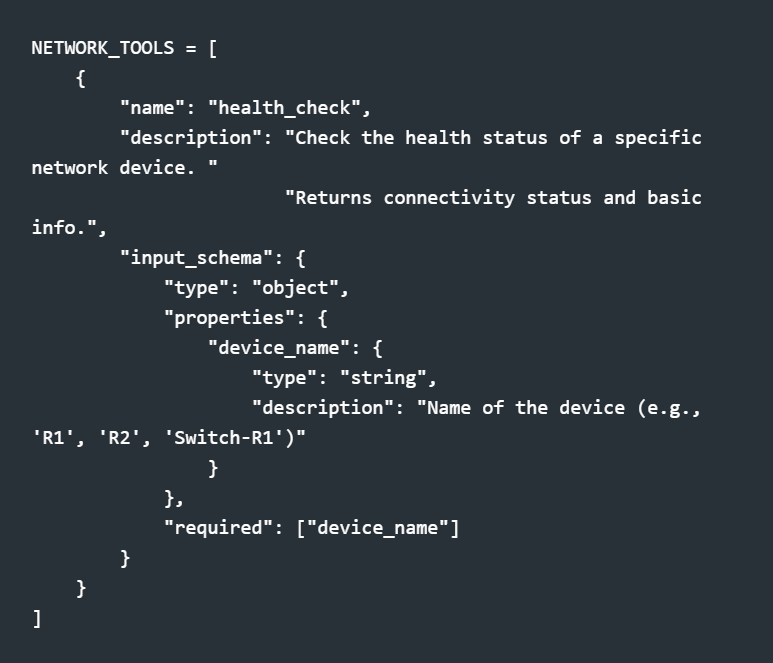

When you define an MCP tool, you're writing documentation for an AI. The schema matters:

Notice the description fields—they're not just comments. Claude reads them to decide when to use each tool. "OSPF neighbors" in the description means Claude will call send_command with show ip ospf neighbor when I ask about OSPF.

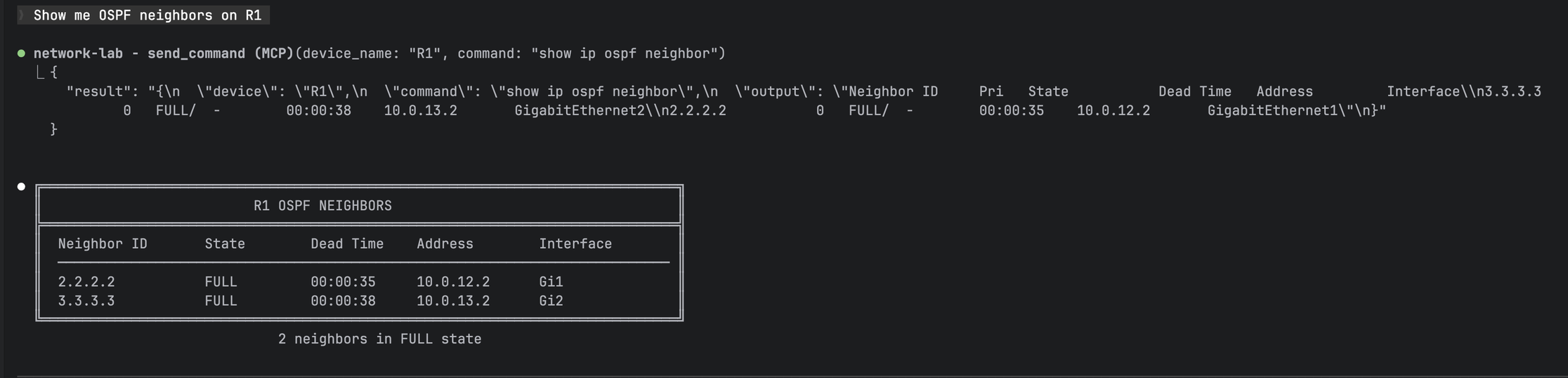

Natural language query "Show me OSPF neighbors on R1" -> MCP tool call -> formatted table output

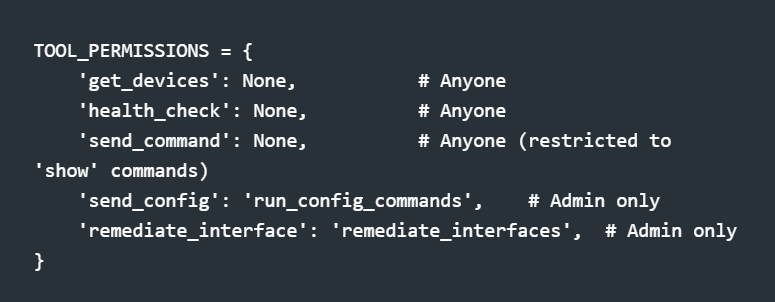

Permission-Gated Tools

Not every user should configure devices. I split tools into read-only (public) and write (admin-only):

A viewer asking "fix that interface" gets a polite explanation about needing admin access. An admin gets the remediation. Same AI, different capabilities.

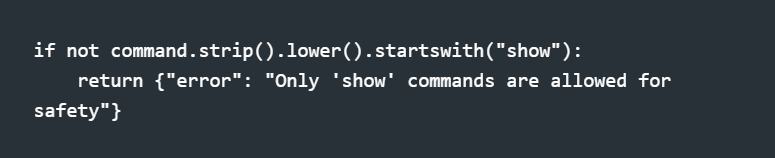

The send_command tool has an additional safety gate:

Even with tool access, you can't accidentally run reload through the chat interface.

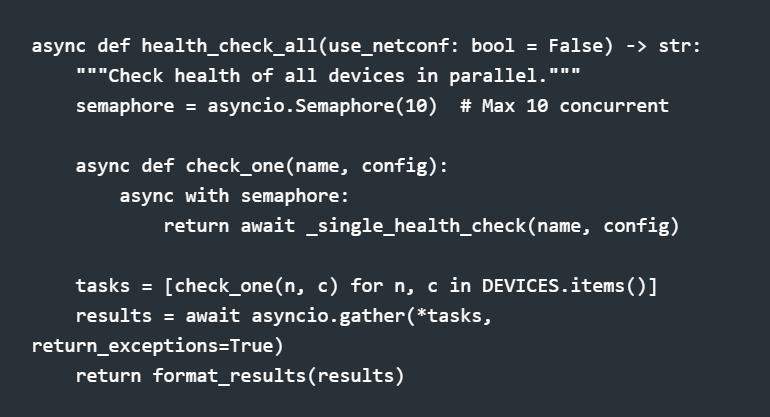

Async Execution: Why It Matters

Network automation means waiting on devices. My first synchronous implementation took 90+ seconds to check 16 devices. The async version: 4 seconds.

The semaphore prevents overwhelming the network. Scrapli handles the async SSH connections. The result is parallel execution with controlled concurrency.

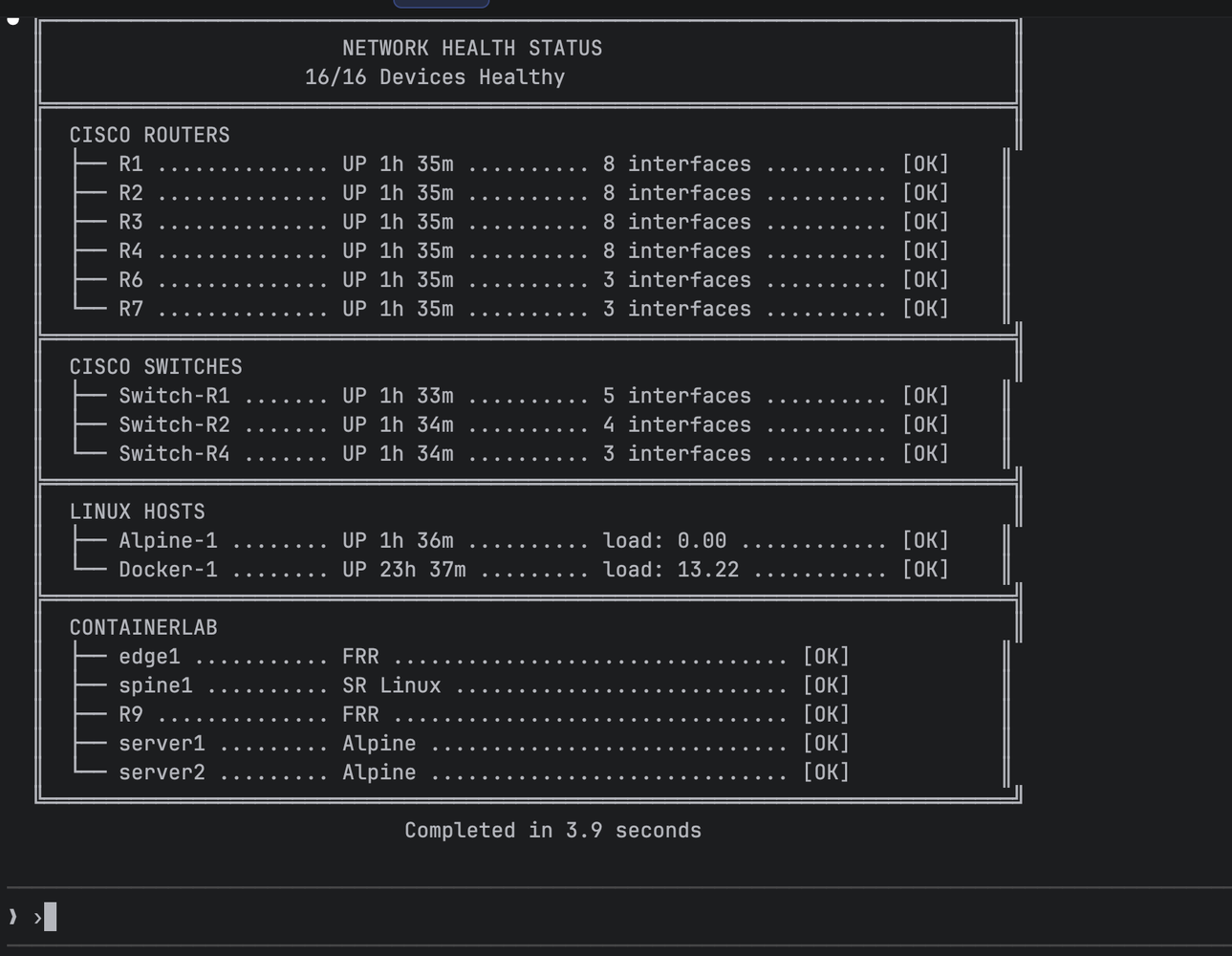

Network Health Status showing 16/16 devices healthy, completed in 3.9 seconds

The Agentic Loop: How Claude Uses Tools

This is where MCP gets interesting. Claude doesn't just call one tool—it chains them based on what it learns:

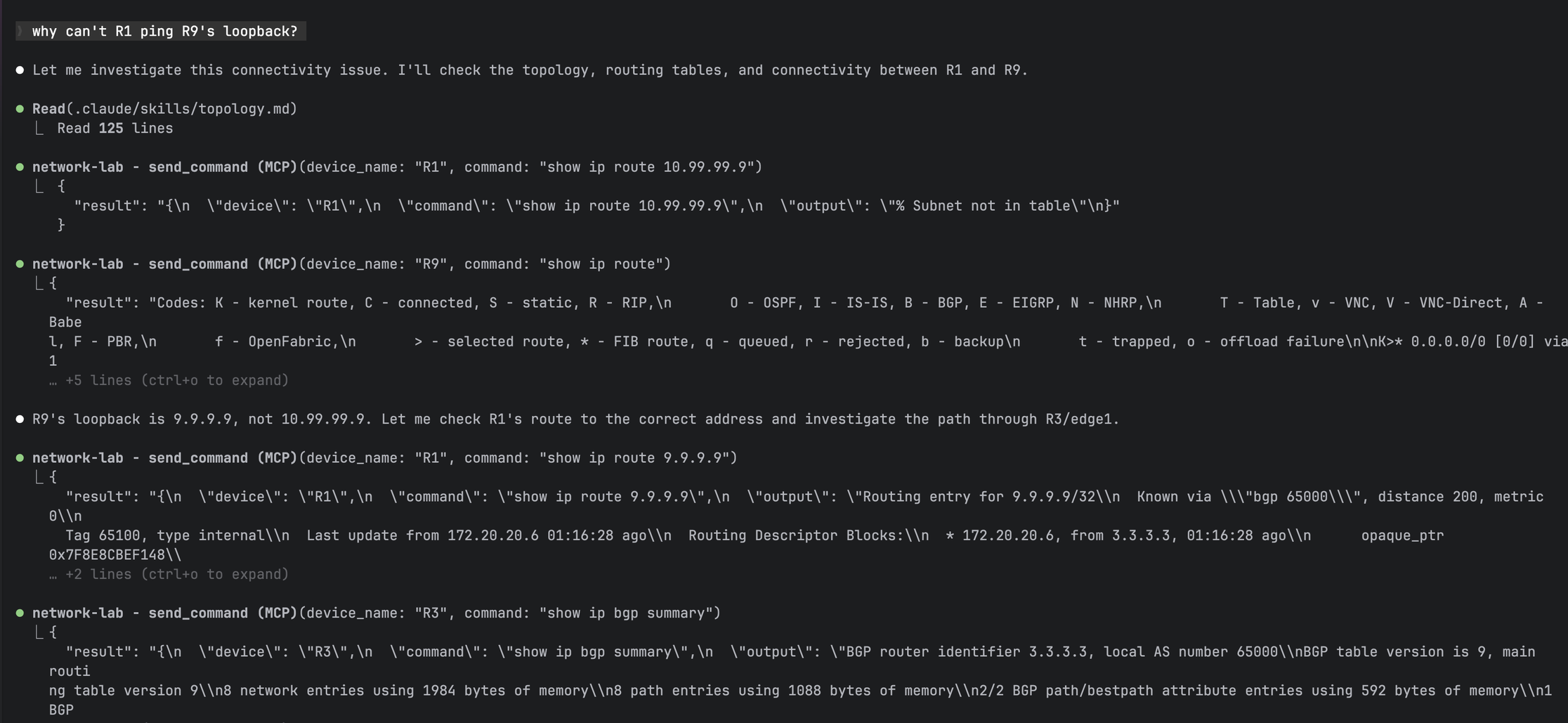

Me: "Why can't R2 reach the 4.4.4.4 loopback?"

Claude's internal flow:

Call send_command("R2", "show ip route 4.4.4.4") → No route found

Call send_command("R2", "show ip ospf neighbor") → R1 missing from neighbors

Call send_command("R2", "show ip ospf interface brief") → OSPF enabled on Gi2

Call send_command("R1", "show ip ospf interface brief") → OSPF on Gi2, different area

Response: "R2 can't reach 4.4.4.4 because OSPF adjacency with R1 isn't forming. R2 has Gi2 in area 0, but R1 has it in area 1. Fix the area mismatch.

Claude chaining multiple tool calls to diagnose "why can't R1 ping R9's loopback"

I didn't script that workflow. Claude figured out the diagnostic sequence from the tool descriptions and intermediate results.

Tool Consolidation Pattern

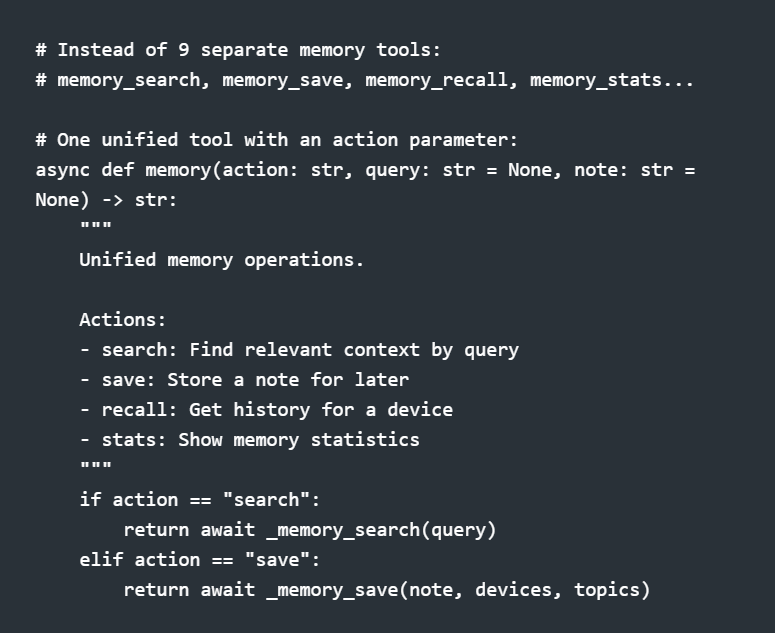

With 142 tools, organization matters. I use an action-based pattern for related operations:

Claude sees one memory tool instead of nine. The action parameter gives it flexibility without cluttering the tool list.

What I'd Build Differently

1. Start modular. My first version was a 7,180-line monolith. The refactor to 27 modules was painful. Start with one tool per file.

2. Design descriptions for the AI. Your docstrings aren't just for humans. Include example use cases: "Use for checking interface status, routing tables, OSPF neighbors."

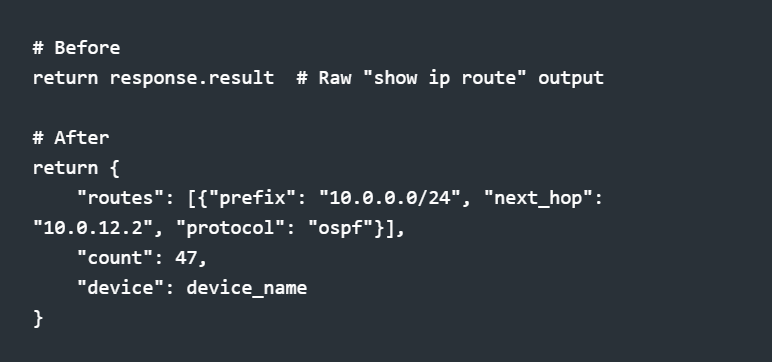

3. Return structured data. Early tools returned raw CLI output. Now I return parsed JSON that Claude can reason about:

4. Add semantic memory early. Without memory, every conversation starts from zero. My memory tool uses ChromaDB for semantic search—Claude can recall that "R1 OSPF issues" were caused by MTU mismatch last week. Of course, this is for my small lab. For production you would want to use something like PostgreSQL + pgvector. But that's for another discussion.

The Numbers

MCP Tools → 142

Tool Modules → 27

Devices Managed → 16

Vendors → 4 (Cisco, Nokia, FRR, Linux)

Health Check (16 devices) → 4 seconds

Lines of Python → 79,500

Getting Started

If you want to build your own MCP server for network automation:

Install FastMCP: pip install mcp

Define one tool: Start with health_check or send_command

Write for the AI: Descriptions matter more than you think

Test with Claude: Use Claude Code or the MCP inspector